The French Divide - To The Limit

My 1600km journey through France on the 2017 French Divide with 100 other riders, starting at Dunkirk and aiming to finish in the Basque country.

Posted: Fri 18 Aug, 2017, 09:44

- Training Day

- Great Expectations

- Easy Riders

- Local Hero

- Counter Intelligence

- Need for Speed

- Breaking Bad

- Final Destination

Training Day

Training for something as epic as the French Divide is nearly impossible. The time required to build up the musculature, leathery contact points and stamina is really not available to most of us with normal lives. A proper training session would be the ride across another country off-road, which is frankly ridiculous. But I had trained as much as possible, which included some ever lengthening rides as the big day approached, including two rides to my work via fairly serious intervening hills - 60 miles in total with 4500 feet of climbing. Coupled with a big days out in blistering temperatures whilst on holiday in Crete I was in as good shape as I could be.

The precise route had been made available to the starters a few weeks before the start. Starting near Dunkirk it headed east along the Belgian border, down through the l'Avernois forest and on to Champagne. From there it traversed the Loire valley before rising into the mountains for Morvan and then the volcanoes of central France. Descending from here the route hits the Massif Central which must be crossed before the ground flattens slightly on the approach to the finale - the Pyrenees via the Tourmalet - before finishing in the fairly random town of Mendionde. The zoomable map below shows the route in all it's glorious and devilish detail.

The countdown to my departure seemed to slow progressively as the day neared, until the day came and I was on the one hand desperate to leave and on the other hand sad to say good bye. With such an unknown ahead, it really felt like a poignant goodbye, that was best tackled making light of the entire situation. So I headed for the sleeper from Glasgow to London followed the train to Dover. Only as I queued for the ferry did I realise the ticket I had purchased not exactly as intended. When booking the ferry, I had only realised at the last minute that I could actually sail to Dunkirk, a good 25 miles closer to the start than Calais. However by then I had two tabs open in the browser both at precisely the same stage of booking, and by mistake, I had returned to the wrong tab and bought a ticket to Calais. I did not realise my error until I was queuing, and realised I had a 30 mile cycle to the start rather than 5 mile ride. No need to panic, but rather a worrying oversight.

After arriving in France I rode for a while and then performed a rather bizarre transformation. I pulled in at quiet layby with picnic tables and got fully changed into all my riding gear. Once I had my lycra, gloves, helmet and cycling shoes on there was nothing to do but put my backpack, jeans, T-shirt and old trainers in the bin and ride off. It was surreal and felt as though I had somehow changed into someone else entirely, which in a way I had.

When I arrived at the start, it was a relief to check-in and cross the last hurdle before the start. Meeting all the organisers was fun but also slightly disconcerting. They had met and started so many other riders before that they probably have a pretty good instinct about how far each rider will get. It was only natural to wonder what they made of me. Their approach both then and throughout the entire Divide was to be helpful but never encouraging. Quite rightly that was not their role, their role was map the route and simply track progress which they did flawlessly. There should be no other dependency on them, it is a self-supported challenge after all. At the same time I found them slightly engimatic and distant, due in part to the language barrier I guess. Over the many days that lay ahead, I did often wonder whether there was a sort of inherent masochism entailed in putting together the often tortuous route we rode. In the end I decided there absolutely was, but that we riders must also share the same tendancies.

I have nothing but respect for the organisers. They have made something incredible. Their organisation was excellent and the same time imbued with a manic gallic humour that only the French have.

Great Expectations

There were two sets of expectations to be managed - my own and my friends & family's.

There were two sets of expectations to be managed - my own and my friends & family's.

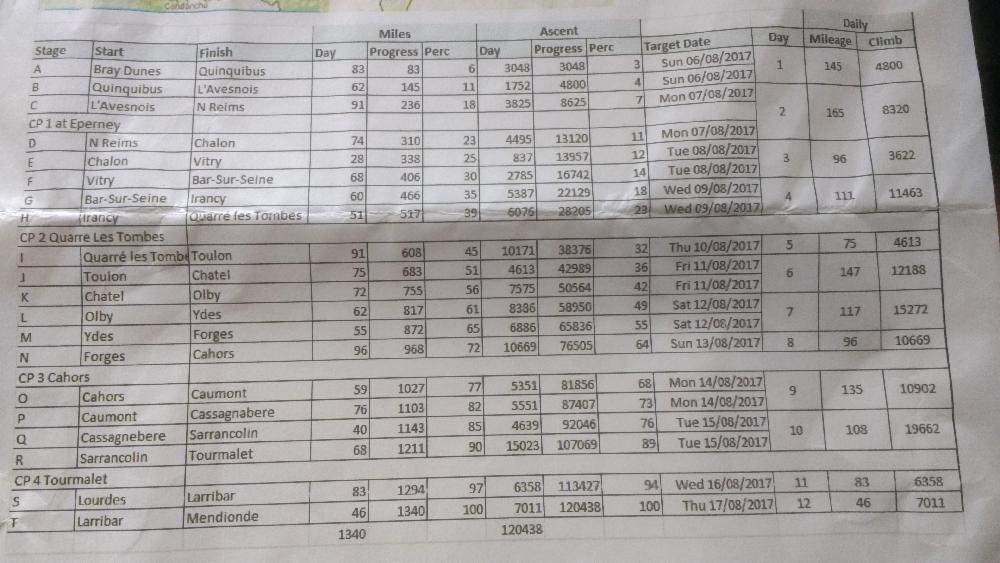

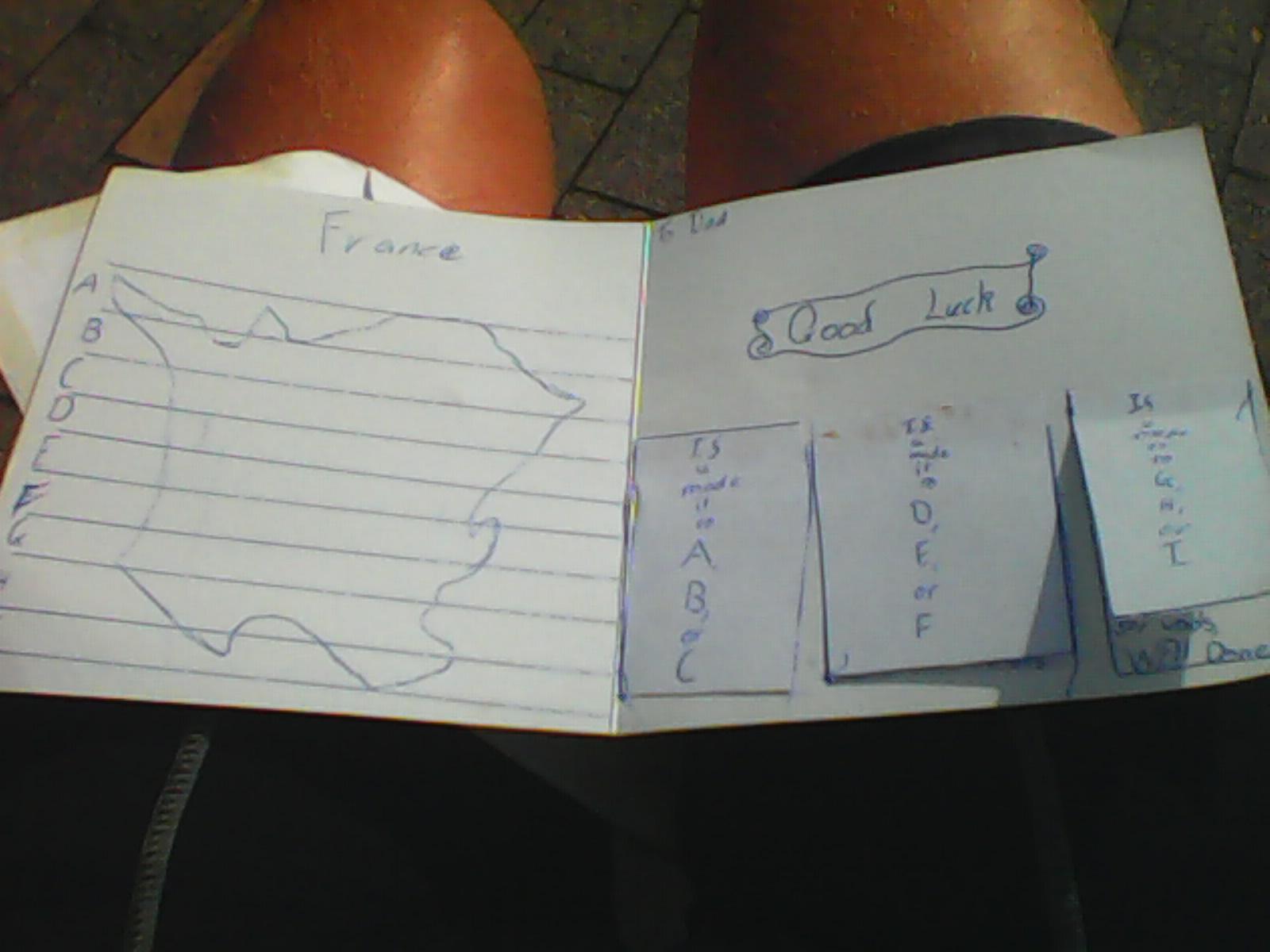

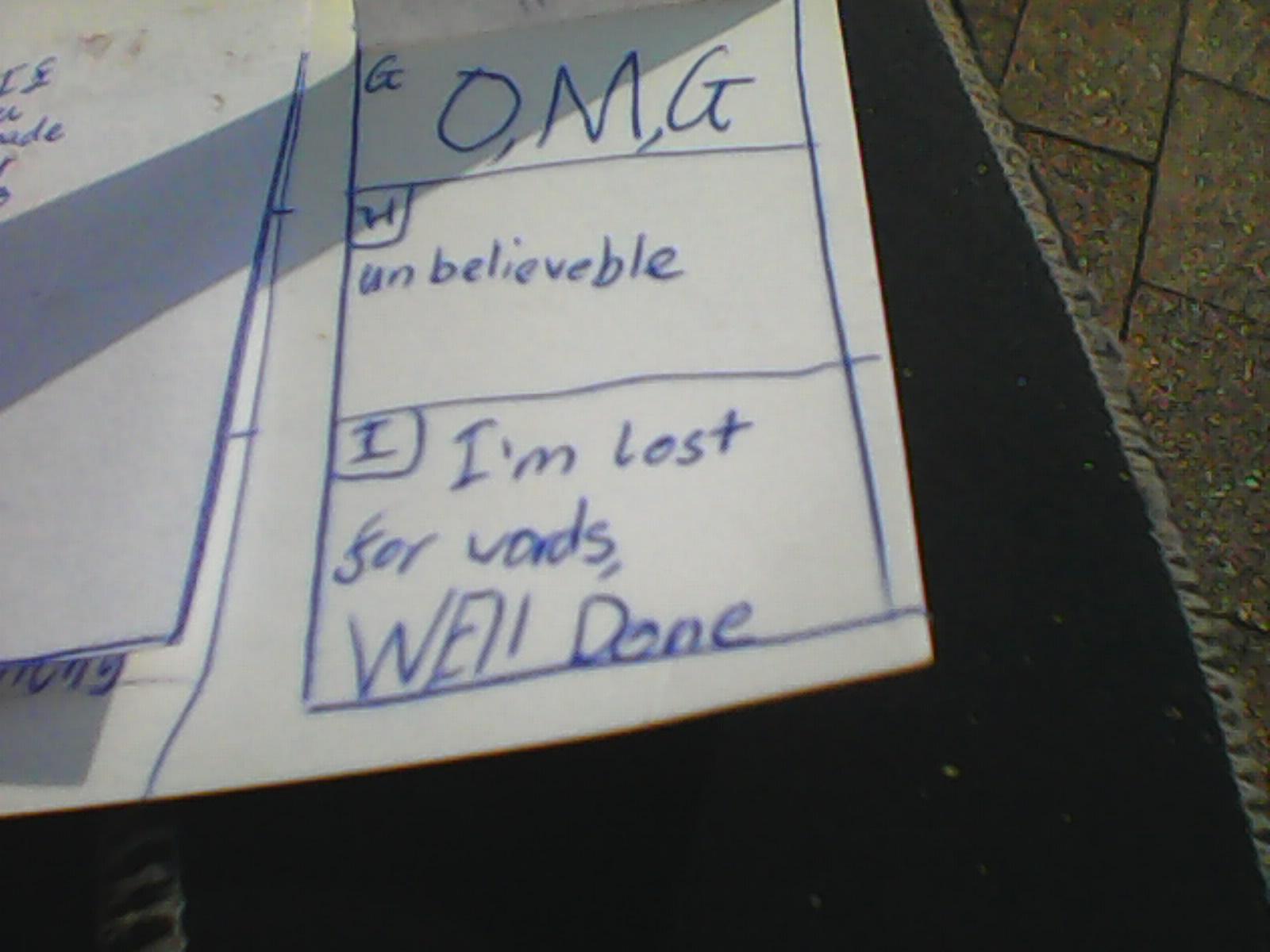

Managing my own expectations was fairly schizophrenic. On one hand I was planning for an early exit due to fatigue, technical failures or who knew what, so took steps to figure out how I would get home from various places in eastern France. On the other hand, in my deepest heart of hearts to which I would never really admit to anyone, was the belief that I may be able to ride the whole way and I needed to plan this out. And so it was that I put together my ride sheet that laid out all the points I needed to hit in order to make it to the end within my required 12 days. This planning was only done at the very, very last minute because it seemed preposterous to even think I would still be riding after day five. But as they say failing to plan is planning to fail, so I had to do it. The required mileages and ascents required, over unknown terrain, were just beyond anything I had ever ridden before so pretty quickly after figuring it out I folded up the ride sheet and packed it away. Better to focus on one day at a time.

To my friends and family my expectations were kept extremely low, based on my previous riding experience and the fact that French Divide was just another one of my bonkers schemes. I have a bit of history of deciding to do somewhat difficult, challenging or outrageous projects so this was probably just another one of them. In order to avoid any worry or concern, I did not share my target mileages, which in retrospect was a mistake. My true intentions on the Divide only really emerged as everyone saw me riding and the ground I was covering and it was probably as much of a surprise to them as it was to me. Had they known in advance I could have planned better with them, but it was a bit like Leicester planning their 2016 Premiership celebrations at the start of the season, it was beyond laughably optimistic!

Tempering my natural over-optimism was actually useful. Had I indeed finished early due to the punctures it would not have been the end of the world. It was exactly what everyone (including me) was expecting and no big deal. It was also good pshycologically to feel like every day after day two was really a bonus and further that you had expected to make it. This was the truth, based on my ruined state after the Cairngorm Loop, so keeping my expectations firmly based in reality meant I was continually surprised and pleased to have completed a stage or made a checkpoint.

Tempering my natural over-optimism was actually useful. Had I indeed finished early due to the punctures it would not have been the end of the world. It was exactly what everyone (including me) was expecting and no big deal. It was also good pshycologically to feel like every day after day two was really a bonus and further that you had expected to make it. This was the truth, based on my ruined state after the Cairngorm Loop, so keeping my expectations firmly based in reality meant I was continually surprised and pleased to have completed a stage or made a checkpoint.

It would been best to have a very clear plan for how and when I was going to get back from finish in Mendionde. To have planned this would have sugested I was always going to finish and take away the whole uncertainty. Many of the other riders had planned precisely this and displayed a level of confidence in their own abilities that I simply did not have.

Easy Riders

Bike-packing, or ultra long-distance bike packing for that matter, are not exactly common pursuits. Trying to explain to people exactly what I was going to do was often difficult, especially when there was nobody else to point to and say "I'm doing that!". So the prospect of starting the French Divide with a bunch of other people who obviously relish the prospect of a multi-day, self-supported ride across the wilds of France was very appealling. Like-minded crazy cyclists! I quickly figured out that most of the riders starting on the Sunday were very experience cyclists - many had ridden the Alps on road, the Rockies or completed the French (or Italian) Divide before. In stark contrast, my most ambitious bike ride to date had been the Cairngorm Loop which took me two days and after which I had to be collected in a shambolic state as I was unfit to get myself home. The gap in experience was obvious.

However, without exception, every single fellow rider I spoke to was friendly and always interesting. Over the coming days there were several times when I was blown away by what these guys were able to do on their bikes. On the night before the start many of us went for a meal at a local restaurant. I arrived at the same time as Ben and we joined a table of what turned out to be the uber pro cyclists who had completed last year. They politely answered my niave questions without saying too much to dispel my obviously crude awarness of what lay ahead. After a while, Ben and I mostly listened and tried to stop asking questions because it was too late to change anything. Whatever was or was not ahead, or whatever kit I did or did not have, it was too late to change. We were starting tomorrow at 6:24am.

Ben

Ben rode on a highly customized single speed bike. Even as we rode around the flat Bray Dunes, it was clear that he rode it at very high cadence. With only one gear, it was a kind of a binary experience, either zipping along at a decent turn on speed or stopped, nothing in between. The prospect of riding over all the hills that lay ahead was not one that I would have relished but Ben had ridden in the Rockies and claimed to have managed without too much bother. I say "claimed" because I honestly found it very hard to believe. Gears are essential no? How are you supposed to get up a steep gravel hill with no run-up? I just could not fathom it but how wrong I was.

Ben rode on a highly customized single speed bike. Even as we rode around the flat Bray Dunes, it was clear that he rode it at very high cadence. With only one gear, it was a kind of a binary experience, either zipping along at a decent turn on speed or stopped, nothing in between. The prospect of riding over all the hills that lay ahead was not one that I would have relished but Ben had ridden in the Rockies and claimed to have managed without too much bother. I say "claimed" because I honestly found it very hard to believe. Gears are essential no? How are you supposed to get up a steep gravel hill with no run-up? I just could not fathom it but how wrong I was.

Ben and I kipped at the same bit of the campsite and it was actually him packing up that woke me - my alarm had not gone off because I had not changed it to France time. Doh, another close shave. He made me an amazing coffee on a super fast stove that he was carrying the whole way, and then we headed off to the start. After the start, I remember seeing Ben on three specific occasions on the ride. The first was climbing past me on the Kemmelberg cobble hill, as I pushed my bike up. He actually rode up. The gradient tops out at 20% which too much for me at that stage of the ride. Somehow he had cranked his bike up and ridden the first serious climb of the route, whilst with all my gears I was already pushing. The second time was slumped in the sheltered doorway of a supermarket on day two, before I had all my punctures. He had arrived ahead of me and on the basis of his collapsed posture and grumbly comments, I really thought he was struggling. Maybe he was, my feeble attempts to offer some encouragement did not seem to help much. After I had eaten, I saddled up and said goodbye and wondered how far Ben was going to get. I did not see Ben again and given our last exchange, I kind of thought he might have stopped, given I did not have the tracker. As we rode through the mountains of the Morvan and volcanoes, I could not concieve of how it would be possible to ride them on a single speed. So on day six, after a terrible start without any food, I had reached Ebreuil by 9am, stocked up and ridden on into the warming day, feeling better and better. My target lunch time stop was still not any closer however by 1:30pm I decided to stop at the top of a hill, eat my lunch and dry out my stuff. As I was slumbering in the glorious midday sun with all my gear strewn around me, who should ride by but Ben. He had made it. Through all the sudden climbs of the vineyards, the mountains and preposterous climbs, and he was looking strong. We had a chat and after a bit he rode on.

Philip

Philip was one of the first people I spoke to at the Sunday check-in. Another fellow Brit, he was living in Belgium now and was another first timer on the French Divide. He looked with some wonder at my choice of bike, with the thick tyres, slack head and long wheel base it could not have been more different to his narrow steel cyclo-cross. (The truth is that you can ride the Divide on almost any bike, so long as you are comfortable on it.) Philip and I rode a roughly similar pace for the first three days as we were often passing each other or for spells we would ride together. He pretty funny guy and most of the time I was with him was spent laughing. On day three we were deep in Champagne territory and tackling the steep vineyards climbs. I clearly recall him setting off from a standing start up a gravelly track with zero grip that progressively steepened, he somehow powered up the incline, crested the top and disappeared. At the time, I would have thought this short stretch was just unrideable, but he somehow figured a way up. Another thing that impressed and amused me about Philip was how he tackled the cobbles of Arenberg - the pave. There are many miles of cobbled trails that famously wind through the Arenberg farmland which are relentlessly bumpy. I remember reaching a transition from gravel to cobbles with Philip at which point I was slowing down, standing up and looking for a smoother route down the edges of the cobbles. Not Philip. His cadence, posture and speed did not change one bit, he just battered on over the cobbles and duly disappeared again.

Philip was one of the first people I spoke to at the Sunday check-in. Another fellow Brit, he was living in Belgium now and was another first timer on the French Divide. He looked with some wonder at my choice of bike, with the thick tyres, slack head and long wheel base it could not have been more different to his narrow steel cyclo-cross. (The truth is that you can ride the Divide on almost any bike, so long as you are comfortable on it.) Philip and I rode a roughly similar pace for the first three days as we were often passing each other or for spells we would ride together. He pretty funny guy and most of the time I was with him was spent laughing. On day three we were deep in Champagne territory and tackling the steep vineyards climbs. I clearly recall him setting off from a standing start up a gravelly track with zero grip that progressively steepened, he somehow powered up the incline, crested the top and disappeared. At the time, I would have thought this short stretch was just unrideable, but he somehow figured a way up. Another thing that impressed and amused me about Philip was how he tackled the cobbles of Arenberg - the pave. There are many miles of cobbled trails that famously wind through the Arenberg farmland which are relentlessly bumpy. I remember reaching a transition from gravel to cobbles with Philip at which point I was slowing down, standing up and looking for a smoother route down the edges of the cobbles. Not Philip. His cadence, posture and speed did not change one bit, he just battered on over the cobbles and duly disappeared again.

The last time I saw Philip is a pretty cool memory. On day three when my puncture nightmare was just in the early stages I think I had stopped for maybe the third time to fix yet another puncture. He'd already passed me earlier when I was fixing another puncture. Previously to that Philip and I had become split up in a technical forested section, however he soon caught me as I toiled away trying to get my back tyre off and slowed to check I was alright. As he cycled by he chucked me one of his two spare 29" inner tubes and insisted I take it. I carried that all of the rest of they way and ended up using after a desent from the volcanoes several days later. It was pretty selfless act given how crucial spares are and the early stage we were at.

Daniele

Daniele was an experienced Italian ride who had ridden the Italian Divide. His demeanour was either deadly serious or cracking up with laughter, but most of the time he laughing infectiously. We chatted a lot at the start and rode together a bit on the first day. The end of the second section, and the end of my first day, we reach that stunning town of le Quesnoy. Le Quesnoy has the most unbelievably huge defensive walls around it, built many years ago brick by pain-staking brick. The route circles the walls, drops in the gulley below and eventually runs right through the wall via narrow subterrainan tunnel with zero illumination, requiring me to fire up my front light for the first time. Daniele and I reached this point at the same time and I was scoping for a good place to bivvy. Not Daniele, he was getting geared up to ride on into the night, on the very first night. I was starting to realise now what that Divide was going to require. I moved ahead of Daniele briefly and cycled through le Quesnoy which was in festival-mode thanks to a visiting fair, and it was busy with people out enjoying the food, fairground rides and beer tents. The Divide riders must have been an incongruous site as we weaved through the crowds.

Daniele was an experienced Italian ride who had ridden the Italian Divide. His demeanour was either deadly serious or cracking up with laughter, but most of the time he laughing infectiously. We chatted a lot at the start and rode together a bit on the first day. The end of the second section, and the end of my first day, we reach that stunning town of le Quesnoy. Le Quesnoy has the most unbelievably huge defensive walls around it, built many years ago brick by pain-staking brick. The route circles the walls, drops in the gulley below and eventually runs right through the wall via narrow subterrainan tunnel with zero illumination, requiring me to fire up my front light for the first time. Daniele and I reached this point at the same time and I was scoping for a good place to bivvy. Not Daniele, he was getting geared up to ride on into the night, on the very first night. I was starting to realise now what that Divide was going to require. I moved ahead of Daniele briefly and cycled through le Quesnoy which was in festival-mode thanks to a visiting fair, and it was busy with people out enjoying the food, fairground rides and beer tents. The Divide riders must have been an incongruous site as we weaved through the crowds.

After Daniele disappeared off into the night I figured he would not be seen again. As I did not have access to the tracker I was unaware that he had also had technical issues and lost time fixing his rear derailleur. So I was surprised to hear on day eight - my best day - that he was behind me. We ended up all meeting up again for a memorable meal at Cahors and he was looking focused, strong and ready for the next stage.

There were many other riders who I spoke with and often rode with. The calibre of rider that started the French Divide on that Sunday (and probably the other days) was pretty exceptional. All were club riders, most were sponsored, almost all had experience of multi-day riding on-road and often off-road. Strangely, I had never really thought of myself as a proper cyclist, more of a mountain biker, and we are a slighly different breed. MTB riders just tend not to put in as many miles as road cyclists, enjoying the slower technical climbs followed by andrenalin decents, always away from the annoyance of motor vehicles. Long days in the saddle against the clock, more common in road biking, basically means day after day of pain. The pain becomes something you can live with, and perhaps even enjoy. I ended up realising that when I was not in pain, I was not pushing, so was always working as hard as I could tolerate. That is what the adventure became, an internal battle with myself. When alone in the saddle in unknown places covering vast tracts of land, often hungry and sometimes cold, it became a very intense experience in my own little world of suffering.

Somehow however, I ended up enjoying it more than I ever expected. Seeing the landscape transition from the hills of Champagne to the mellow Loire Valley to the mountains of Morvan was endlessly fascinating. I used to think of my distances in terms of horizons. How many horizons do I need to cross today? On typical land with hills it can be 20 odd miles to cycle to the most distant point in sight. This was the slightly crazy scale of the French Divide.

Local Hero

After the eurphoria of reaching the first checkpoint at Epernay on my target timeframe, my energy level quickly crashed and it took all my energy to climb out of Epernay to find a place to bivvy. In truth, I was completely torn between finding a hotel and camping out. My concern with staying in a hotel was that it would be too comfortable and discourage me from leaving at the ungodly hour my schedule required. So it was that I bivvyed in the vineyards overlooking Epernay. My first choice of site was very poor, basically in dirt and close to a road. When I had not fallen asleep at midnight reluctantly packed up and moved on a few miles and found a much more comfortable grassy spot where I fell asleep pretty quickly. In the morning, as I got ready to go, I realised my back tyre was flat - my first puncture.

After the eurphoria of reaching the first checkpoint at Epernay on my target timeframe, my energy level quickly crashed and it took all my energy to climb out of Epernay to find a place to bivvy. In truth, I was completely torn between finding a hotel and camping out. My concern with staying in a hotel was that it would be too comfortable and discourage me from leaving at the ungodly hour my schedule required. So it was that I bivvyed in the vineyards overlooking Epernay. My first choice of site was very poor, basically in dirt and close to a road. When I had not fallen asleep at midnight reluctantly packed up and moved on a few miles and found a much more comfortable grassy spot where I fell asleep pretty quickly. In the morning, as I got ready to go, I realised my back tyre was flat - my first puncture.

The memory of all the following punctures is slightly vague but by the end of day three I had suffered seven punctures in total, across both my front and back wheel. Every one was a blow, created a creeping uncertainty and lost me valuable hours. After every fix there was a nervy spell of double checking to make sure the tyre was still fully inflated, followed by a period of confidence and then the crushing realisation that it was flat again. My procedure for fixing the flats was to get the wheel off, get one side of the tyre off and pull out the tube. I had packed only one tyre lever which was just not enough, and by the end of the day my fingers were bleeding from prizing off the tubeless ready tyre off. I would then check the tube to find the puncture and patch it. At the same time I would run my hands over inside of the tyre to make sure there was no thorn or nail sticking through. As the punctures accumulated however, particularly on the back wheel, my confusion grew as I finally began to realise that there must be something in the tyre to cause all the flats. Something I could not see or feel.

Just before the final puncture at Maizieres-les-Briene I had told myself that if I had one more then my French Divide was probably over. I had only one spare left, hardly any patches and had lost over four hours making my chances of keeping the already ambitious schedule extremely slim. After a longish spell late in the afternoon, after a huge thunderstorm, the back tyre again went flat. My frustration was beyond description. I had the phone in my hand ready to call home and say it was over but then my logical head kicked in one last time. It was also an inspiration to recall Mark Beaumont's book about this ride across Africa where he told of this endless punctures across Ethiopia, and although our situations and abilities could not have been more different, it helped me to not give up. As the sun shone down between thunderstorms, I realised that I had three inner tubes all punctured in the same place - on the side and just passed the diagonal opposite from the valve. I checked the rear tyre at this point - on both sides given I did not know what way the inner tubes had been fitted - and felt absolutely nothing. But there must be something there so I looked closely on the side and saw tiny hole on the inner fabric of the tyre. On the outside tred at this precise point was a thick chunk of rubber that actually had a tiny indentation. I got my pliers, prized open the hole and delved in... to find a tiny shard of yellow glass (see last picture below). This tiny fragment had holed tube after tube, caused my numerous delays and energy sapping sessions reinflating a 29" tyre back to 50 psi every time by hand.

Just before the final puncture at Maizieres-les-Briene I had told myself that if I had one more then my French Divide was probably over. I had only one spare left, hardly any patches and had lost over four hours making my chances of keeping the already ambitious schedule extremely slim. After a longish spell late in the afternoon, after a huge thunderstorm, the back tyre again went flat. My frustration was beyond description. I had the phone in my hand ready to call home and say it was over but then my logical head kicked in one last time. It was also an inspiration to recall Mark Beaumont's book about this ride across Africa where he told of this endless punctures across Ethiopia, and although our situations and abilities could not have been more different, it helped me to not give up. As the sun shone down between thunderstorms, I realised that I had three inner tubes all punctured in the same place - on the side and just passed the diagonal opposite from the valve. I checked the rear tyre at this point - on both sides given I did not know what way the inner tubes had been fitted - and felt absolutely nothing. But there must be something there so I looked closely on the side and saw tiny hole on the inner fabric of the tyre. On the outside tred at this precise point was a thick chunk of rubber that actually had a tiny indentation. I got my pliers, prized open the hole and delved in... to find a tiny shard of yellow glass (see last picture below). This tiny fragment had holed tube after tube, caused my numerous delays and energy sapping sessions reinflating a 29" tyre back to 50 psi every time by hand.

My frustration with myself for not thinking of the actual cause sooner was quickly offset by the relief that perhaps I had finally found the problem and maybe, just maybe, my French Divide was not over yet. As I reinflated the tyre for the last time my hand pump disintegrated, probably it was never designed to be used as intensively. With that it was clear that I really could not have any more punctures. As I had been working on my bike, rider after rider passed me, some stopping to chat like Anna and Graham, but all slowing to check that all was good. Again, my bouyant mood at possibly having fixed the issue finally countered my disappointment at losing so much time. Just think where I could have been had I been able to ride all afternoon?

As I was packing up my stuff to cycle on a local guy cycled up to me to check if I was alright and had everything I needed. If he had asked me an hour earlier he would have had a very different answer but at that point I was actually all sorted, and said thanks but I was all good and ready to go. He asked where I was going to stay and I said probably in the next town - or a field near the next town. He introduced himself as Stephane and explained he had actually put up another French Divider the night before in his garage and that, if I wanted, I was welcome to stay there tonight. After briefest of consideration, I said absolutely. Stephane then went on to say we would all eat together and if I wanted there was a shower. This all seemed too good to be true but when I cycled round ten minutes later, it was exactly as he had said. His house was in fact the ex-garage for the village so had a large forecourt and a proper garage building on the side of this house. Within was a mattress and space for me to sort out my bike and wet stuff.

As I stood in the shower, it was hard to imagine how a complete stranger could be so incredibly hospitable. On top of the demoralising day I had endured, this seemed like a bit good fortune and perhaps a sign of things to come. Stephane's wife Caroline had prepared dinner, which we ate in their kitchen. Both were extremely interesting people and Stephane's English was fortunately excellent so we were able to talk easily. He had made a living for many years in IT (like me) and then decided to quit for the good life in this beautiful village. He had the tracker open on the iPad and had wondered why there was someone stopped for so long at the edge of his village. Their obviously outgoing and hospitable nature had won out and they had decided to put up another rider. I will be forever grateful to both, it was one of the most generous things anyone has ever done for me. Stephane even drove to get croissants in the morning which we ate at 6am. I was back on the road for 6:20am, feeling completely refreshed, with a ping-tight back wheel and hoping for a good day ahead.

As I stood in the shower, it was hard to imagine how a complete stranger could be so incredibly hospitable. On top of the demoralising day I had endured, this seemed like a bit good fortune and perhaps a sign of things to come. Stephane's wife Caroline had prepared dinner, which we ate in their kitchen. Both were extremely interesting people and Stephane's English was fortunately excellent so we were able to talk easily. He had made a living for many years in IT (like me) and then decided to quit for the good life in this beautiful village. He had the tracker open on the iPad and had wondered why there was someone stopped for so long at the edge of his village. Their obviously outgoing and hospitable nature had won out and they had decided to put up another rider. I will be forever grateful to both, it was one of the most generous things anyone has ever done for me. Stephane even drove to get croissants in the morning which we ate at 6am. I was back on the road for 6:20am, feeling completely refreshed, with a ping-tight back wheel and hoping for a good day ahead.

Counter Intelligence

One of my motivations for doing the French Divide was to experience the polar opposite of my day to day working life. My working life is physically sedantary and mentally intensive, I sit at a desk all day and figuring often difficult things out. To be able to exercise all day, towards an incredible goal, and not think too much, was absolutely part of the draw. Also the experience of disconnecting for a short while and going off grid was also appealling, as I can find the noise of our daily connectedness overwhelming sometimes. With this in mind, and also to keep thing simple and save on power, I decided to take a ruggedized Nokia phone to stay in touch with everyone, but without internet access. This would ensure my focus on biking and keep my charging requirements down.

One of my motivations for doing the French Divide was to experience the polar opposite of my day to day working life. My working life is physically sedantary and mentally intensive, I sit at a desk all day and figuring often difficult things out. To be able to exercise all day, towards an incredible goal, and not think too much, was absolutely part of the draw. Also the experience of disconnecting for a short while and going off grid was also appealling, as I can find the noise of our daily connectedness overwhelming sometimes. With this in mind, and also to keep thing simple and save on power, I decided to take a ruggedized Nokia phone to stay in touch with everyone, but without internet access. This would ensure my focus on biking and keep my charging requirements down.

Another reason for not taking a smart phone was that it would mean I could ignore the Track Leaders tracker which showed everyone's position. My only race was with time, to keep my schedule and allow me to complete the Divide, get home, recover and be back at work on the Monday. Watching the tracker brings in a whole other relative dimension that emphasises where we each are in relation to other riders. If I was dropping off the back of the pack, I really did not want to know. And if I was just ahead of someone, I really did not want to know either. My pace maker was my schedule and that was all. So having not smart phone ensured I would not be distracted.

For the vast majority of my ride, I had no regrets about my decision. My phone was excellent, took basic photos, played my mp3s and was my alarm as well. It needed charged once every three days for not very long and I received countless texts from friends and family along the way. However, in retrospect, a smart phone is a real essential that I should have taken. The primary benefit is information (or as I called it intelligence). Knowledge about where you are, what is nearby, how far to the next campsite, how good the bike shop in the next town is or booking a room in a hotel 50 miles away. Information like that can become crucial and is honestly what nearly ever other rider had at their disposal. In my naivity, and my wish to break free from my information overload, I overlooked the sheer practical necessity of a smartphone. As a result, I spoke to so many people looking for directions or to find out where the nearest bike shop is, which was pretty cool. However, I never knew where I was going to sleep until the last minute, which became increasingly difficult as the ride wore on. (Sending texts on an old style phone was very slow too, so I lost a fair amount of time on that!)

For the vast majority of my ride, I had no regrets about my decision. My phone was excellent, took basic photos, played my mp3s and was my alarm as well. It needed charged once every three days for not very long and I received countless texts from friends and family along the way. However, in retrospect, a smart phone is a real essential that I should have taken. The primary benefit is information (or as I called it intelligence). Knowledge about where you are, what is nearby, how far to the next campsite, how good the bike shop in the next town is or booking a room in a hotel 50 miles away. Information like that can become crucial and is honestly what nearly ever other rider had at their disposal. In my naivity, and my wish to break free from my information overload, I overlooked the sheer practical necessity of a smartphone. As a result, I spoke to so many people looking for directions or to find out where the nearest bike shop is, which was pretty cool. However, I never knew where I was going to sleep until the last minute, which became increasingly difficult as the ride wore on. (Sending texts on an old style phone was very slow too, so I lost a fair amount of time on that!)

I think it is absolutely possible to do the French Divide without a smart phone, but for me it was just another small and gradual set back. The Divide is of course supposed to be ridden without l'assistance and you could argue that a smartphone is the ultimate l'assistance, and actually I was riding it on a purer basis. Possibly it was purer, but the internet is available to everyone so completely allowable, and sensible, to use it to help you.

Philip always had good intelligence. He knew exactly where the next McDonald's was. Priceless.

Need for Speed

One thing I learned, to my surprise, was that I was pretty fast. Dispite all the time lost with punctures, losing my helmet (and having to detour to buy another), I was still, somehow, roughly on schedule when I reached Cahors. On the first three days my average pace over the full day was sufficient that some of the fellow riders, who I would see again and again over the following days, only caught me after seven punctures.

One thing I learned, to my surprise, was that I was pretty fast. Dispite all the time lost with punctures, losing my helmet (and having to detour to buy another), I was still, somehow, roughly on schedule when I reached Cahors. On the first three days my average pace over the full day was sufficient that some of the fellow riders, who I would see again and again over the following days, only caught me after seven punctures.

Speed on the French Divide is achieved by either riding fast, riding for a long time or both. Those that finish it quickly are definitely doing both. My daily pattern ended up being that I had roughly six hours sleep, and although I made so many mistakes, I think I got that about right. Six hours of good rest is just about enough for me and up until at least day eight I was managing well on this. Those six hours have to be good rest however, so the importance of comfort and warmth cannot be over stated.

But actually on the bike, I was way faster than I expected, which was down to a few key aspects I think. Firstly when my big and heavy 29" wheels get up to speed, on tyres at 50 psi, with my 36 tooth front cog and stretched out on the aero-bars, on flat ground my speed was often between 16mph and 20mph. I could keep going at this speed for long stretches and not tire. I was comfortable, my breathing was stable and I reached a steady state, with just my legs pumping and everything else relaxed. I cannot think of a single time when someone overtook me in the sort of situation. On day two I rode by a guy on his road bike who was out for a wee spin and, unknown to me, he immediately got down and caught me up. After a mile or two I had to slow to turn off onto a gravel track at which point he pulled up next to me, out of breath, and exclaimed "Trente kilometre!" i.e. he could not believe that on my bike, bulky MTB I was cruising along at that speed.

Aero-bars on a mountain bike are funny. If an MTBer saw your riding with that they would say "What a ****". If a road biker saw you, they would say the same. And yet they were something I would not have done without. I only summoned up the courage to fit them on a few days before the start but very quickly got used to them. On gravel roads I could even ride using the aero bars, weaving between the potholes, and quickly pulling up for the brakes if needed. I never came off when on the aeros and they were so comfortable. Aerodynamic benefit was also important. Although the literature will tell you benefits only really kick in above 30 kph, it's not a binary thing, there are undoubtedly benefits are lower speeds (particularly into the wind). They are worth it for the comfort alone.

Aero-bars on a mountain bike are funny. If an MTBer saw your riding with that they would say "What a ****". If a road biker saw you, they would say the same. And yet they were something I would not have done without. I only summoned up the courage to fit them on a few days before the start but very quickly got used to them. On gravel roads I could even ride using the aero bars, weaving between the potholes, and quickly pulling up for the brakes if needed. I never came off when on the aeros and they were so comfortable. Aerodynamic benefit was also important. Although the literature will tell you benefits only really kick in above 30 kph, it's not a binary thing, there are undoubtedly benefits are lower speeds (particularly into the wind). They are worth it for the comfort alone.

When climbing to certain gradients, I also think I was pretty fast. My single big cog at the front meant climbing was going to be hard because it is just not possible to spin up anything steep. On my highest gear, it was often still necessary for me to stand up and really grind up the hills. On flatter gradients, I could climb when on the aero-bars. But it meant I had no choice but to climb relatively fast - I simply could not go any slower - and overall I think I was faster than average of climbs. Again, nobody every overtook me on a long climb.

Breaking Bad

There were a whole catalogue of errors that led to me stopping at Cahors, almost all down to lack of experience. One of these errors may not have been enough to stop me, but cumulatively, they meant that my French Divide sadly came to an end at Cahors.

There were a whole catalogue of errors that led to me stopping at Cahors, almost all down to lack of experience. One of these errors may not have been enough to stop me, but cumulatively, they meant that my French Divide sadly came to an end at Cahors.

My most obvious technical error was deciding not to run tubeless tyres. I only bought the bike frame in April, built the bike in a few weeks and simply did not have time to transition to tubeless. Everyone else (that I spoke to) was running tubeless and they obviously work. Some people certainly ran with inner tubes as well, but I was certainly too slow to discover the real cause of my punctures and this meant I lost almost half a day of riding.

My second, more subtle problem, was with my back brake disk. On day four I heard a rattling and looked back to find my back disk was off-kilter and wobbling around. I quickly stopped and discovered that the two of the three screws that held on the disk had pulled out of their threads, meaning only one screw was holding it on. Why only three when there should be six? An oversight on my part when transferring over the rotors from my old bike. I tried to reinsert the loose screws but the threads were gone. After a very worried few minutes I remembered I had some spare screws in a tin, when I tried them on a couple of the good screw sockets they fitted perfectly. However, they were aluminium, not steel. A fact that did not concern me then but would later on.

On day eight, after several days of huge climbs and decents, I used the back brake and there absolutely no tension on the lever, it was totally loose. I pumped it some more but no better, it was as though there was no fluild. I looked back and saw that the rear rotor disc was spinning free and completely detached from the hub. After quickly stopping to investigate, my problem was clear. The aluminium bolts had somehow survived days of decending but on a relatively flat section they had somehow finally sheared, and the final steel bolt had been ripped out, pulling a chunk of hub aluminium with it. The loose rotor had somehow hit the caliper at speed, damaged it and drained all the break fluid. My entire back wheel, rotor and brake assembly were broken and beyond repair. They all needed to replaced. Annoyingly, this as all down to the three missing screws that were clearly required in these extreme conditions.

On day eight, after several days of huge climbs and decents, I used the back brake and there absolutely no tension on the lever, it was totally loose. I pumped it some more but no better, it was as though there was no fluild. I looked back and saw that the rear rotor disc was spinning free and completely detached from the hub. After quickly stopping to investigate, my problem was clear. The aluminium bolts had somehow survived days of decending but on a relatively flat section they had somehow finally sheared, and the final steel bolt had been ripped out, pulling a chunk of hub aluminium with it. The loose rotor had somehow hit the caliper at speed, damaged it and drained all the break fluid. My entire back wheel, rotor and brake assembly were broken and beyond repair. They all needed to replaced. Annoyingly, this as all down to the three missing screws that were clearly required in these extreme conditions.

Buying these new parts at short notice in Glasgow would be pretty difficult, never mind in the middle of rural France on a holiday long weekend. To ride on would have meant riding without a back brake which was possible for a day or two but not sensible for the Pyrenees where two brakes would be critical. My only hope would have been to ride on and hope to cobble something together a bike shop two days away - if one existed. A long shot.

Food and water were my other big mistake. It goes without saying that cycling for up to 15 plus hours a day uses massive amounts of energy. The food required to replenish your reserves, keep the engine burning and give your the power you need to continue was far beyond what I expected. I ate a lot, but still not enough. Making time to sit down somewhere, order two main courses and two deserts was absolutely required but due to my inexperience, I always made do with less. Day eight was one of my best days, when I covered a huge amount of ground and climbs, and it was also one of the days when I ate best. I had endless pastries, peaches, grapes, a baguette, a pizza, a bowl of chips etc. I ate as well that day as any other and I never felt tired even at 8pm when I climbed 1600 feet out straight up out of Forges without hardly breaking sweat. I can hardly believe it now, but it was effortless.

However my lack of food meant I was forever depleting as the ride wore on. This is fairly standard for all riders, everyone will lose weight, but after a point there are no reserves left and you simply must eat well. Some of the best riders I was with, Anna and Graham for example, happily bought and ate unbelievable quantities of food. They knew what was needed and they maintained their energy levels.

However my lack of food meant I was forever depleting as the ride wore on. This is fairly standard for all riders, everyone will lose weight, but after a point there are no reserves left and you simply must eat well. Some of the best riders I was with, Anna and Graham for example, happily bought and ate unbelievable quantities of food. They knew what was needed and they maintained their energy levels.

My final error, and the one that absolutely ended my French Divide, was drinking bad water. Day nine riding through the Massif Central was the toughest, the hottest and my least enjoyable day since the start. My energy levels were low without enough food, progress was slowed by the extreme heat and I simply did not have enough water at certain stages. On more than one occasion I stopped to fill up my bottle from small a small burn. I can still remember the one that I think was bad. In the mountains of Morvain and the volcanoes I had done the same with no ill effects, because the water was fresh and clear up there. But I drank water that was flowing out of a grassy pasture field. Not a good idea, and I am almost sure this was what gave my a bad stomach. By the time I arrived at Cahors, my bike was broken and now I was broken. I took standard remedies and a rehydrate sachet and they both helped, but this final burden on an already expended body left me with no energy.

For all the errors that were somehow guiding me to stop, there were two moments of sheer good fortune that day which seemed to suggest that I continue. In the crazy heat as I neared Cahor I was riding up a trail when I saw a girl up ahead pushing her bike up the same trail. I jumped off as I neared and we started chatting. After some explanation, she was soon helping me get the telephone numbers of bike shops in Cahors so that I could call ahead and see if they could were open and could help. As we did this her two fellow riders ran back to find out where she had got to. We found a shaded spot, one of them (Sylvain I think) helped me look at a problem with my now very creaky bottom bracket. After deciding there was nothing to be done, we got the bike back together and I asked what size of tyres he had. 29". Do you have a spare inner tube?! Yes! He gave me a spare inner tube and absolutely refused to accept any money. Yet another unbelieveable gesture of French generosity that gave me my first fresh inner tubes in days. After thanking them profusely, they filled up my water bottles and waved me off. Maybe this was going to work out after all.

And then in Cahors I realised I had lost my front light charging cable. Not just a simple a USB cable, the specific cable required for my light that had particular jack. This really was a show stopper. As other riders came into the checkpoint however, there was talk of someone finding a cable. Before long Maxence rode in and Anna asked him if he had that cable. He paused briefly, both exhausted and starving, before reaching forward and say "This one?". He had spotted my cable at a random spot and somehow decided to bring it along, in case it was important for someone. What a star.

And then in Cahors I realised I had lost my front light charging cable. Not just a simple a USB cable, the specific cable required for my light that had particular jack. This really was a show stopper. As other riders came into the checkpoint however, there was talk of someone finding a cable. Before long Maxence rode in and Anna asked him if he had that cable. He paused briefly, both exhausted and starving, before reaching forward and say "This one?". He had spotted my cable at a random spot and somehow decided to bring it along, in case it was important for someone. What a star.

I woke up the next day, saddled up and rode out of Cahors with zero enthusiasm and feeling very bad indeed. My last hope was that somehow I would feel better once I warmed up. However four miles out of Cahors on a gravel path - exactly like the hundreds of miles of other gravel paths I had ridden - my front wheel stumbled on a loose rock, I did not correct or unclip in time and landed heavily my side at very low speed, cutting my hand open. As I lay there, I decided that was it. I had literally ridden until I fell off.

Final Destination

Deciding to stop was a difficult decision but also quite obviously the right thing, by the time I was lying in the dirt with a very broken bike. I trundled back down the road into Cahors and started letting everyone know my decision. My friend Christian was quick to suggest some possible solutions to allow me to continue but soon accepted that it really was over. Bob actually called me immediately, which is very rare, as if to double check he had read the message correctly. Once I had itemized my long list of issues, it was clear to him as well that I was going no further. Soon the texts turned to cautious congratulations, everyone aware that along with pride at getting so far there must be disappointment. And there was, it was a tough one to take. Having come so far, ridden over terrain, climbs and distances that I never thought I could realistically achieve, it was pretty crushing to realise I was not going to finish. But by any measure however, I had exceeded expectations and was pretty delighted to ridden this far.

Deciding to stop was a difficult decision but also quite obviously the right thing, by the time I was lying in the dirt with a very broken bike. I trundled back down the road into Cahors and started letting everyone know my decision. My friend Christian was quick to suggest some possible solutions to allow me to continue but soon accepted that it really was over. Bob actually called me immediately, which is very rare, as if to double check he had read the message correctly. Once I had itemized my long list of issues, it was clear to him as well that I was going no further. Soon the texts turned to cautious congratulations, everyone aware that along with pride at getting so far there must be disappointment. And there was, it was a tough one to take. Having come so far, ridden over terrain, climbs and distances that I never thought I could realistically achieve, it was pretty crushing to realise I was not going to finish. But by any measure however, I had exceeded expectations and was pretty delighted to ridden this far.

It was delightful to let all the parts of my life that I had kept to the back of my mind back in. I could not wait to see my wife, my family, to eat properly, to be clean and be at home. The desire for home was a recurring theme on my bike. The further and longer I rode, the more home elevated in mind into an enveloping sanctuary where there was no pain, no cold, no baking heat and only comfort. I was completely home sick for probably the first time in my life.

My journey home was smoothed tremendously by the fact that Christian lived in Toulouse. So after some phone calls we agreed to meet at Toulouse station, where Christian and family planned to be after, coincidentally, riding home from their very own family multi-day ride along the Midi-Canal. As I ate ice cream outside Toulouse station and langorously watched the world go by, they soon appeared and after some brief shock at my bedraggled appearance, guided me back to their house. I felt a lot like a drifter who was now rejoining society, unused to it's polite customs and expectations. The next 24 hours was filled with drinking beer, tremendous home cooking, booking flights, sleeping, visiting Decathlon, dismantling my bike into a bike bag. I feel very lucky to have such friends and yet again feel indebted to have enjoyed such unquestioning hospitality at short notice. Before long I was deposited at the airport in a mixture of borrowed and new clothes and bidding them farewell. I was home in less that four hours.

My journey home was smoothed tremendously by the fact that Christian lived in Toulouse. So after some phone calls we agreed to meet at Toulouse station, where Christian and family planned to be after, coincidentally, riding home from their very own family multi-day ride along the Midi-Canal. As I ate ice cream outside Toulouse station and langorously watched the world go by, they soon appeared and after some brief shock at my bedraggled appearance, guided me back to their house. I felt a lot like a drifter who was now rejoining society, unused to it's polite customs and expectations. The next 24 hours was filled with drinking beer, tremendous home cooking, booking flights, sleeping, visiting Decathlon, dismantling my bike into a bike bag. I feel very lucky to have such friends and yet again feel indebted to have enjoyed such unquestioning hospitality at short notice. Before long I was deposited at the airport in a mixture of borrowed and new clothes and bidding them farewell. I was home in less that four hours.

At time of writing, some two weeks after I returned, I am most certainly still recovering. My appetite is slowly returning to normal, but for the first week I could not stop eating. I have numbness in my left hand that I think is very slowly getting better. Every time I go to sleep I have dreams about riding the French Divide, although they are slightly less vivid now and mixed in with other dreams. For the first half of my ride I was perplexed at the thought of people chosing to ride this for a second time. For the second half, I was truly in my element, feeling stronger every day and I understood why it is so intoxicating. The open air, the landscapes, sleeping under the stars, the epic vastness and beauty of the country we were exploring all heightened my senses and awareness, making each day seem like a week because of the huge sensory explosion. Meeting all the fellow riders, the camaraderie and competition, the huge respect that I had for everyone who had shared this experience. It was something very special, that I somehow shared with all my friends and family thanks to the spot tracker and the texts, so much so that it feels like we all went through it all together.

At time of writing, some two weeks after I returned, I am most certainly still recovering. My appetite is slowly returning to normal, but for the first week I could not stop eating. I have numbness in my left hand that I think is very slowly getting better. Every time I go to sleep I have dreams about riding the French Divide, although they are slightly less vivid now and mixed in with other dreams. For the first half of my ride I was perplexed at the thought of people chosing to ride this for a second time. For the second half, I was truly in my element, feeling stronger every day and I understood why it is so intoxicating. The open air, the landscapes, sleeping under the stars, the epic vastness and beauty of the country we were exploring all heightened my senses and awareness, making each day seem like a week because of the huge sensory explosion. Meeting all the fellow riders, the camaraderie and competition, the huge respect that I had for everyone who had shared this experience. It was something very special, that I somehow shared with all my friends and family thanks to the spot tracker and the texts, so much so that it feels like we all went through it all together.

The French Divide has definitely left it's mark on me. Would I do it again? In truth, I may not get the opportunity to do it again for many reasons, making this experience all the more special. It was about as much I could manage to maintain a semblance of a normal life whilst simultaneously planning to disappear to two weeks to do the mountain bike ride of my life. But, should the chance arise again, then without a doubt I would be there at Bray Dunes to do it all over again. And maybe finish this time.

The French Divide has definitely left it's mark on me. Would I do it again? In truth, I may not get the opportunity to do it again for many reasons, making this experience all the more special. It was about as much I could manage to maintain a semblance of a normal life whilst simultaneously planning to disappear to two weeks to do the mountain bike ride of my life. But, should the chance arise again, then without a doubt I would be there at Bray Dunes to do it all over again. And maybe finish this time.

| Day | Start | End | Distance (miles) | Asc (ft) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bray Dunes | Le Quesnoy | 150.6 | 4199 |

| 2 | Le Quesnoy | Epernay | 132.6 | 6304 |

| 3 | Epernay | Maizieres-les-Brienne | 84.0 | 3044 |

| 4 | Maizieres-les-Brienne | Near Avallon | 132.8 | 9607 |

| 5 | Near Avallon | Autun | 72.7 | 5738 |

| 6 | Autun | Fleuriel | 104.7 | 7891 |

| 7 | Fleuriel | La Bourboule | 77.7 | 8196 |

| 8 | La Bourboule | Above Forges | 118.2 | 10328 |

| 9 | Above Forges | Cahors | 88.8 | 6024 |

| Total | 962.1 | 61331 | ||

Table above is from my own GPS computer, which does not measure ascent too well. Officially that was 76505 feet of climbing.

Thanks for everyone for their support before, during and after the Divide. To Jackie, Daniel, Noah, Kim, Norm (for the motivational texts), to Derek (for the 'Allo 'Allo texts), Bob, Stephen, David, Alain & Louise, Doreen & Ian, Stephane & Caroline, Christian, Sandrine, Eulalie & Charlotte and to everyone else who directly and indirectly helped me along the way.